Discussion Point:

Nigeria does not need to mine copper for copper to matter; it only needs to execute the infrastructure

cycle copper is signaling.

For decades, the US dollar has anchored the global financial system, not because it is perfect, but because it is

liquid, trusted, and supported by deep capital markets. That role is not collapsing, but it is no longer taken for

granted. In recent years, the growing use of financial sanctions, rising geopolitical fragmentation, mounting

fiscal strain, and questions around institutional independence have pushed investors and policymakers to

reassess concentration risk in the system. However, this shift is not sudden or chaotic. It is deliberate, forward

looking, and driven by preparation rather than panic

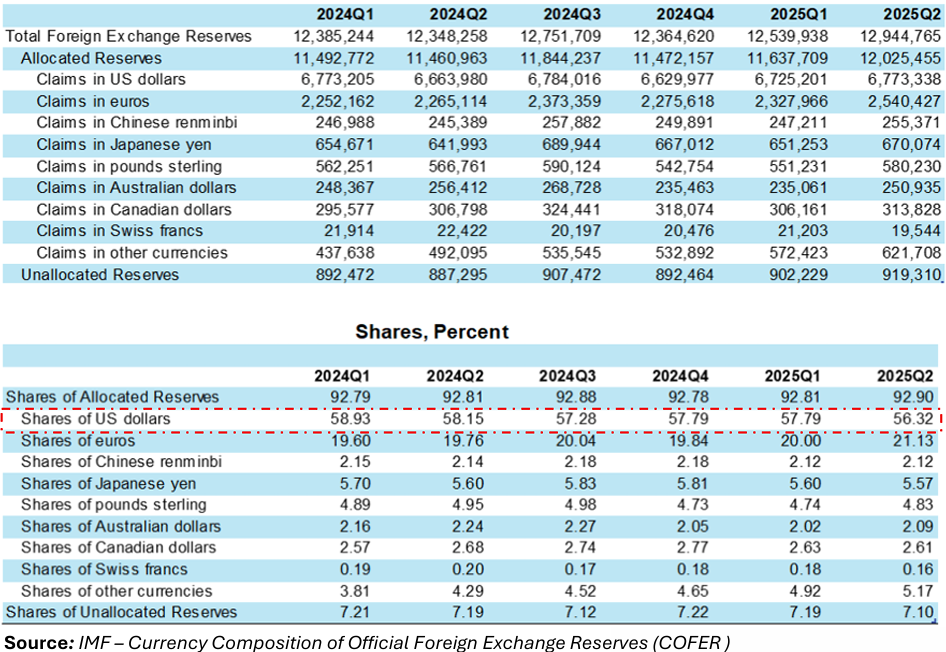

IMF COFER report and data shows that the dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves has declined over

the long term, falling from about 72 percent in the early 2000s to roughly 57 percent today. The table above

captures the most recent phase of that adjustment, with the dollar’s share easing further between 2024 and

mid-2025. This is not evidence of sudden de-dollarisation, but of slow, structural diversification that has played

out over decades. Reserve allocations have gradually broadened beyond the dollar, reflecting a desire to

reduce concentration risk rather than abandon the existing system. The message is subtle but important: the

world is not abandoning the dollar; it is reducing reliance on any single anchor.

When Trust Is Tested, Capital Looks for Safety

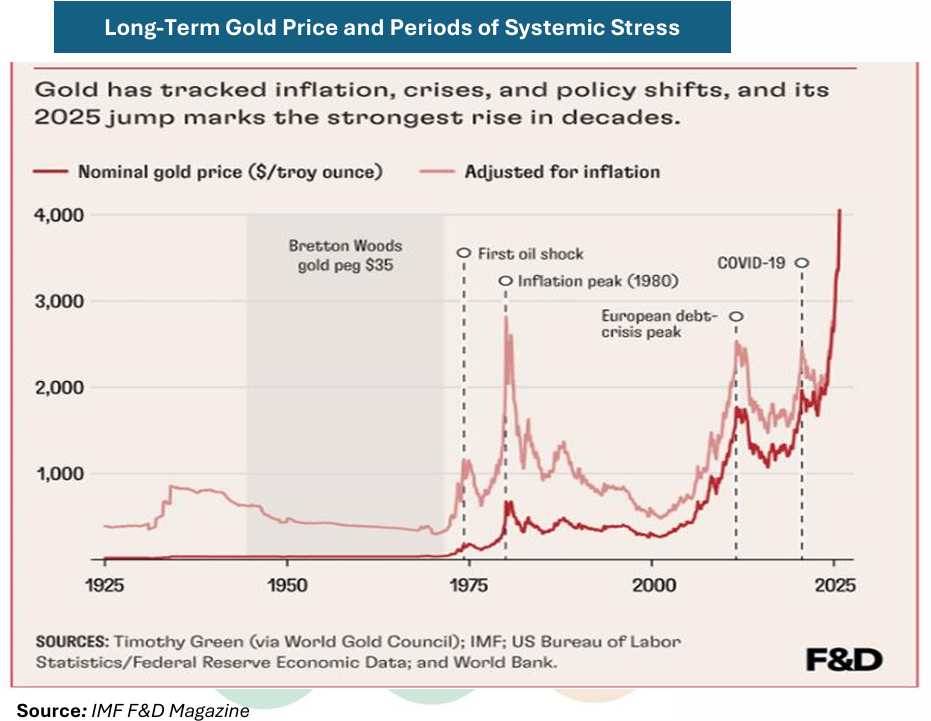

History shows that when trust in monetary and financial arrangements is tested, capital tends to move toward

assets perceived to sit outside the fiat system. This pattern has repeated across major episodes of stress from

the Global Financial Crisis to the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis, and again following the post-2020 inflation

surge and geopolitical shocks. In the current cycle, gold has been the most visible beneficiary of this behaviour.

Gold prices have risen sharply as investors seek protection rather than growth. Gold acts as insurance when

confidence in monetary systems weakens. But markets do not stop at insurance.

After Protection Comes Rebuilding

Markets don’t stop at defence. Once fear is priced in, capital moves on. It rotates toward assets tied to

rebuilding, especially where policy direction and fiscal commitment are clear. We’ve seen this before. After the

Global Financial Crisis, investors rushed into safe assets, then rotated into industrial commodities and

infrastructure during the recovery. The same pattern followed the Eurozone debt crisis.

That shift is happening again. Gold has done its job. It absorbed the fear. Now attention is turning to what

governments and companies are actually building.

This is where copper enters the conversation. Copper is fundamentally different from gold. It is not held for

comfort. It is used to make things work. Power grids, electrification, transport systems, data centres, none of

these exist without copper. Its value is practical, not symbolic. As the International Energy Agency has

repeatedly stressed, there is no large-scale energy transition without materially higher copper use.

Why Copper Has Started Behaving Differently

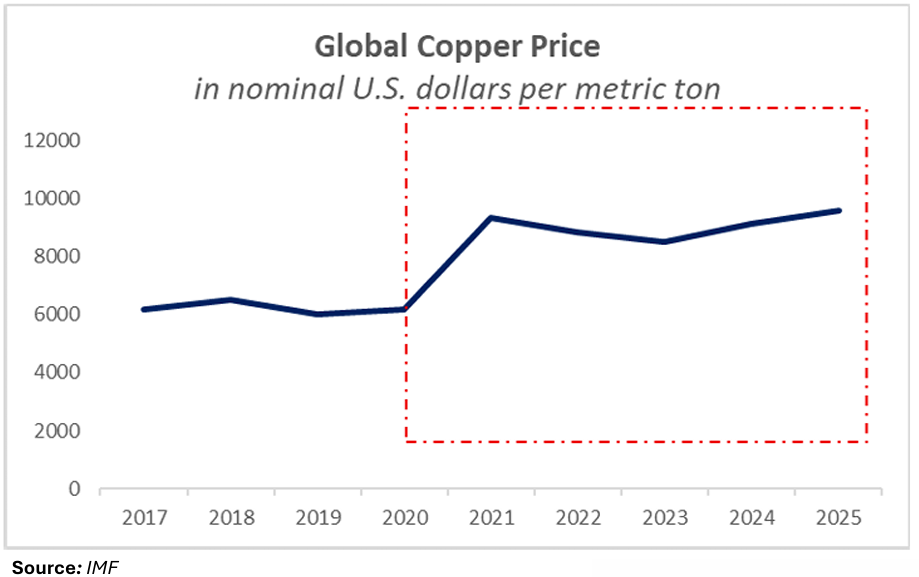

Since 2020, copper has broken from its old playbook. For much of the past two decades, prices tracked the

global growth cycle, rising during expansions and falling during slowdowns. That pattern changed after the

pandemic. Copper prices surged from 2020 and, more importantly, refused to fall back to pre-pandemic levels

even as central banks delivered the most aggressive monetary tightening in decades between 2022 and 2024.

Historically, such tightening would have crushed industrial metals. This time, it didn’t.

Other Current Accounts Components in Q3 2025

The persistence of high prices tells a clear story: copper demand is no longer driven mainly by short-term growth

cycles. It reflects structural investment. The International Energy Agency and the World Bank both point to the

same drivers which are electrification, grid expansion, renewable energy, electric vehicles, data centres, and

large scale infrastructure upgrades, all of which require far more copper than legacy systems.

Crucially, much of this demand is locked into policy frameworks and long-dated capital programmes, from grid

modernization plans to clean energy targets and strategic industrial policies. That makes copper demand less

sensitive to near-term slowdowns. In simple terms, copper is being repriced for how it is used. The market is no

longer treating it as a cyclical signal, but as a core input into the physical systems being built for the next phase

of the global economy.

So what Changed After 2020

Copper’s post-2020 rally did not come from a single trigger. Several forces shifted at the same time.

First, monetary conditions flipped. After the COVID-19 shock, central banks injected extraordinary liquidity into

the global system. The US Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet aggressively, while real interest rates

across advanced economies turned deeply negative. Federal Reserve and IMF data show that real yields on US

Treasuries remained below zero for much of 2020–2022. In such environments, capital historically moves toward

real assets. Gold responded first, rising as a store of value. Copper followed, not as a fear hedge, but as a

beneficiary of how that liquidity was ultimately deployed into construction, power systems, and industrial

capacity. This gold first, copper-next sequence mirrors the post-2008 cycle, but on a much larger scale.

Second, fiscal policy returned in force. Unlike the decade after the Global Financial Crisis, the post-2020

recovery was not led by central banks alone. Governments stepped back into the economy. In the United States,

the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act explicitly targeted power grids, clean

energy, EV supply chains, and domestic manufacturing. In Europe, the NextGenerationEU programme prioritised

energy security and electrification. China accelerated grid expansion, renewables, and strategic industrial

capacity.

These programmes are copper-intensive by design. The International Energy Agency estimates that clean energy

technologies require materially more copper than fossil-fuel systems, embedding copper demand directly into

fiscal execution rather than discretionary spending.

Third, the global business cycle changed shape. Post-2020 growth has been less consumption-led and more

capital-expenditure-driven. Supply-chain fragility, energy security concerns, digitalisation, and geopolitical

fragmentation pushed economies toward rebuilding physical systems such as power transmission, data

centres, transport networks, and industrial redundancy. The IMF and World Bank have both documented this

shift toward investment-heavy growth. Copper sits at the centre of this transition because it is a core input into

electrification and infrastructure. These projects are multi-year, policy-backed, and far less sensitive to short

term sentiment. That structural shift explains why copper broke out after 2020 and did not return to pre

pandemic ranges.

Copper as a Productive Asset, Not Just a Commodity

IMF research using Chile as a case study helps clarify copper’s evolving role. In earlier cycles, commodity booms

often destabilised economies. During the 1970s and early 2000s, sharp rises in copper prices were frequently

associated with overheating, currency appreciation, and boom-bust fiscal cycles. The IMF has shown how weak

fiscal rules and rigid exchange-rate regimes amplified volatility, turning commodity windfalls into macro risk.

More recent experience tells a different story. IMF analysis shows that with credible fiscal frameworks,

transparent revenue management, and flexible exchange rates, copper price upswings can support income,

external balances, and investment without destabilising the economy. Chile’s use of structural balance rules

and sovereign wealth buffers is often cited as evidence that commodity revenues can be absorbed productively

rather than destructively.

For investors, the implication is clear. Copper now rewards structure and execution, not chaos. Demand today is

tied less to speculative excess and more to productive capacity: grids, electrification, industrial systems, and

long-dated infrastructure investment. In that sense, copper behaves less like a boom-bust commodity and more

like a macro transmission asset: one that reflects how effectively policy intent is converted into physical

investment.

What This Means for Nigerian Equities

This discussion is not centred on Nigeria’s copper demand or import volumes, but on price signals and

investment transmission.

Nigeria is not a copper producer par se, so the relevance of rising copper demand is not about mining exposure.

The transmission runs through how copper is used globally. Copper demand is rising because the global

economy is rebuilding power systems, transmission networks, data infrastructure, and industrial capacity.

These projects are capital-intensive, multi-year, and policy-driven. When this type of investment accelerates

globally, it shows up locally through execution, not extraction. Over time, global investment cycles tend to work

their way through to local economies. In that sense, copper functions as a signal of whether the world is building

or stalling, much like how global semiconductor cycles matter for markets that do not produce chips

themselves.

For Nigerian equities, this matters in three clear ways. First, power generation and energy infrastructure benefit

from sustained grid investment. Companies such as Transcorp Power and Geregu Power are positioned to gain

as transmission upgrades reduce technical bottlenecks, improve dispatch reliability, and support more

predictable cash flows. Grid stability turns installed capacity into usable revenue.

Second, construction and engineering firms benefit from longer project pipelines. Companies like Julius Berger

Nigeria typically see stronger order books when governments and utilities commit to transmission lines,

substations, and large-scale energy projects. These are not one-off contracts, but rolling programmes that

improve asset utilisation and earnings visibility.

Third, cement producers gain from the civil works that accompany electrification and industrial expansion.

Dangote Cement, WAPCO and BUA Cement benefit indirectly as grid expansion, power projects, and industrial

facilities require foundations, roads, and supporting infrastructure. Cement demand in this context is structural

rather than cyclical.

At the same time, higher global copper prices act as a filter within the equity market. Companies with heavy

reliance on imported inputs and weak pricing power face margin pressure, particularly where FX exposure is

unhedged. This mirrors the cocoa example in reverse: rising input costs benefit some players but compress

margins for others.

The implication is that copper’s signal for Nigerian equities is selective, not broad-based. It favours companies

exposed to infrastructure execution, power stability, and construction activity, rather than firms dependent on

cheap imports or short-term consumption.

Gold and Copper Are Sending Different Messages

Gold and copper are responding to the same macro shift, but at different points in the cycle. Gold typically

moves first when confidence in monetary systems is questioned, as seen during the Global Financial Crisis, the

Eurozone debt crisis, and again after the post-2020 inflation surge. Its recent strength reflects demand for

protection and value preservation.

Copper’s signal is different. According to the International Energy Agency and World Bank, copper demand rises

with investment in power grids, renewable energy, electric vehicles, and infrastructure. It is consumed, not

stored. In simple terms, gold protects value when trust is tested, while copper reflects commitment to rebuilding

and productivity.

The Takeaway for Investors

The global system is not experiencing a collapse of the dollar. Trust is being spread more carefully, and investors

are paying closer attention to where resilience comes from. That shift has already shown up in markets. Gold has

done its job as a safe place to hide when uncertainty was high, and prices it’s now reflects fear. Copper, on the

other hand, is reacting to what comes next which is rebuilding, electrification, and long-term investment.

So the real question for investors is where to go from here. Buying gold after it has already break All time high

which carries its own risks. Developed markets have already moved higher, leaving less room for upside

compared with markets that are still adjusting. This is why attention is slowly turning back to emerging markets,

where valuations are lower and returns can still surprise on the upside.

In that context, markets like Nigerian equities deserve a closer look. Last year, Nigerian stocks have delivered

strong returns, even in dollar terms, driven by domestic reforms and a market repricing rather than global

liquidity alone. For equity investors, the opportunity is not about chasing commodities themselves, but about

positioning in markets and companies that stand to benefit from the next phase of global investment. Copper is

not just reflecting today’s economy, it is pointing to where growth and capital are heading next.

Kindly find the Report Below

Thanks for reading.