Discussion Point:

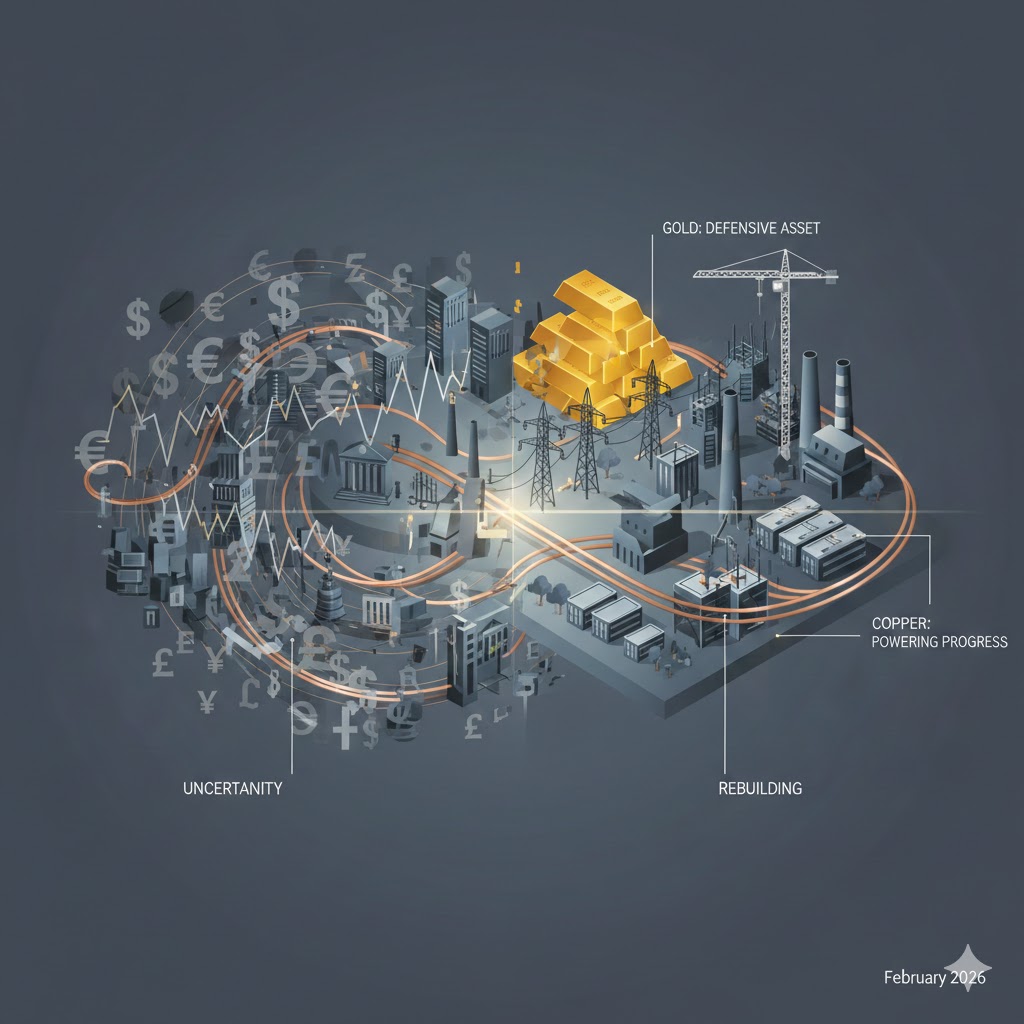

Structural Liquidity Fix: The Federal Government is engineering a structural fix to the power sector’s chronic N4tn debt burden, converting old, doubtful obligations into clean, government-guaranteed tradeable instruments via the N590bn first tranche bond issuance.

After years of mounting arrears that strained power generation and gas supply, the Federal Government has begun addressing the ₦4 trillion debt owed to GenCos, starting with a ₦590 billion bond. But before we dive in proper, let’s examine the performance of power sector according to Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) Q2 report

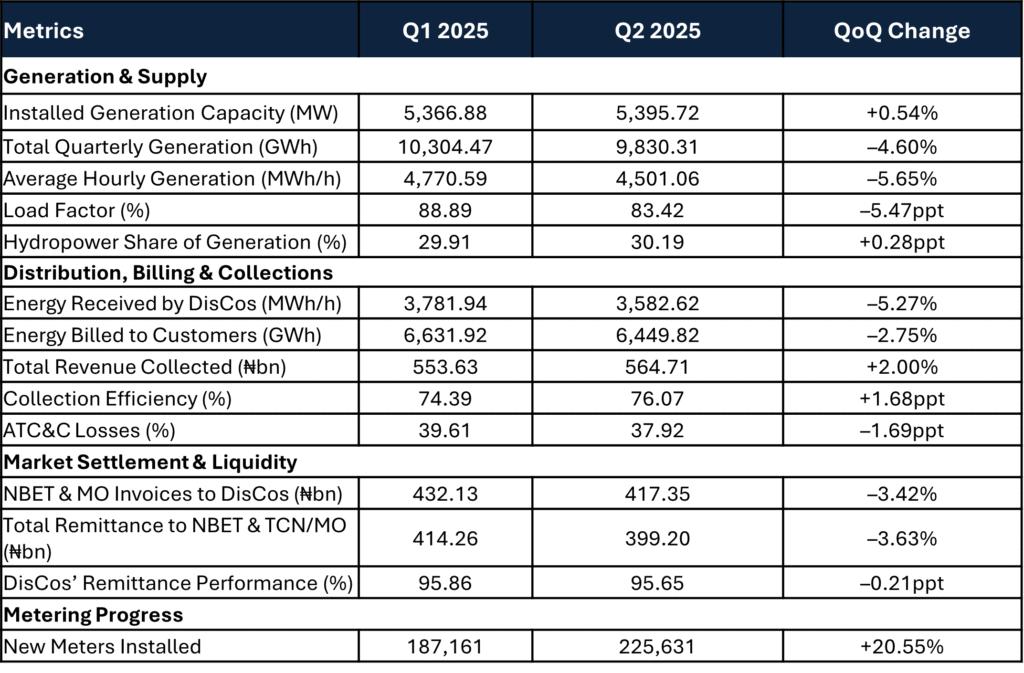

Nigeria’s electricity industry performance in Q2 2025 compared to Q1 2025

What The Numbers Are Showing Us

Installed generation capacity increased marginally by 0.54% to 5,395.72MW in Q2 2025. However, this improvement in capacity did not translate into higher output. Total quarterly generation declined by 4.6% to 9,830.31GWh, while average hourly generation fell by 5.65% to 4,501.06MWh/h. This divergence highlights a key structural issue in the power sector: capacity exists, but it is not being fully utilised. The constraint is less about installed assets and more about gas supply disruptions, maintenance backlogs, grid limitations, and persistent liquidity pressure across the value chain.

Load factor also declined by 5.47 percentage points to 83.42%, reinforcing the fact that generation assets were used less efficiently during the quarter. At the same time, the share of hydropower in total generation increased slightly by 0.28 percentage points to 30.19%, suggesting that hydro plants helped cushion the drop in thermal generation, likely due to gas-related challenges. However, this marginal support was not enough to offset the broader decline in overall power output.

On the downstream side, energy received by DisCos declined by 5.27% to 3,582.62MWh/h, while energy billed to customers fell by 2.75% to 6,449.82GWh, reflecting weaker supply into the distribution network. Despite lower energy volumes, total revenue collected by DisCos rose by ₦11.08bn (+2.0%) to ₦564.71bn, driven by better billing discipline and improved collections. Collection efficiency increased to 76.07%, supported by a 20.55% rise in new meter installations and a 1.69 percentage-point improvement in ATC&C losses to 37.92%. In simple terms, DisCos collected better, but from less energy.

However, improved collections did not fully flow upstream. Total remittance to NBET and the Market Operator declined by ₦15.05bn (-3.63%) to ₦399.20bn, while overall remittance performance slipped slightly to 95.65%. Although combined NBET and MO invoices reduced by 3.42% to ₦417.35bn, the persistence of remittance gaps explains why GenCo receivables have continued to accumulate. This liquidity mismatch where cash improves downstream but weakens before reaching generation is precisely what the Federal Government is now attempting to correct through the NBET bond programme, by converting unpaid obligations into government-backed instruments to stabilise the value chain.

The Logic Behind the Bond Programme

With this background above, the bond structure becomes easier to understand. The problem was not that power plants did not exist, or that DisCos were not collecting anything at all. The problem was a cash-flow break in the middle of the value chain, where NBET accumulated obligations it could not settle on time. To fix this, the Federal Government opted for a structured bond programme rather than ad-hoc cash payments. The ₦4 trillion NBET Bond Programme is designed to clear debts in phases, starting with a ₦590 billion first tranche.

According to Presidential Power bond Programme, this first tranche is split into two parts, ₦300 billion is issued as cash bonds available to the broader market, while the remaining ₦290 billion is issued as non-cash bonds directly to GenCos on the same terms. These bonds are fully guaranteed by the Federal Government, recognised for CBN liquidity purposes, and compliant with PenCom guidelines. This structure matters because it immediately converts years of unpaid invoices into instruments that GenCos can either hold, trade, or use as collateral. In practical terms, it turns uncertainty into liquidity and restores confidence across the power value chain.

Where this Leaves NGX Stocks

Once these bonds enter the system, the impact flows through to listed equities. The first beneficiaries are the power generation companies listed on the NGX. For companies like Transcorp Power and Geregu Power, a significant portion of their receivables sits with NBET. Clearing this backlog improves their cash position, strengthens their balance sheets, and supports better turbine maintenance, more reliable generation, and future expansion plans. These are not theoretical benefits; they directly address the operational constraints highlighted in the NERC data.

Beyond the GenCos, the effect extends to gas suppliers and integrated energy companies. When GenCos are paid, gas suppliers face lower default risk and more stable demand. This supports companies like Seplat Energy, Aradel, Oando, TotalEnergies, and Eunisell, whose revenues are linked to gas-to-power activity. A more predictable power sector also improves visibility for infrastructure and construction companies. As liquidity stabilises, transmission upgrades, substation projects, and EPC contracts become more bankable, bringing companies like Julius Berger, BUA Cement, and Dangote Cement into focus.

Why the Market Is Paying Attention

In essence, the bond programme is not just about settling old debts. It is about resetting confidence in the energy value chain. By removing the biggest source of uncertainty which is unpaid receivables, the government has reduced the risk premium that equities investors have been forced to price into power, gas, and infrastructure stocks for years. This is the channel through which the ₦590 billion bond translates into real equity-market implications.

A Note of Caution

While the bond programme is a step in the right direction, it also raises an important question. Before government intervention, there should be a full review of how these debts were accumulated in the first place. The backlog did not build up in isolation; it came from years of tariff distortions, weak remittance discipline, policy reversals, and governance gaps across the value chain. Publishing a clear, verifiable breakdown of these obligations would help restore trust and ensure that the same problems do not resurface after the bonds are issued.

Without this level of transparency, there is a risk that the bond programme treats the symptom rather than the root cause. Clearing debts without fully addressing how they were incurred could set a precedent where inefficiencies are repeatedly socialised. For the market, accountability matters just as much as liquidity. Investors will be watching closely to see whether this intervention is followed by stricter oversight, improved remittance enforcement, and stronger regulatory discipline going forward.

All data used in this report was sourced from NERC Q2 report, Presidential Power Sector Bond Programme and energy reform report

Kindly find the Report Below

Thanks for reading.